Applying the DDM: Why social psychologists should care

Last update: May, 2019

As a social psychologist, you may be wondering, why should I care about using the DDM? It's a fancy tool, for sure, but what can it tell me that I don't already know? Well, I'm very glad you asked!

Let me give you one example from my lab (Harris, Clithero, & Hutcherson, 2018) that I hope you'll find interesting. We'll work through the logic of the example, and I'll share the code used in the published paper relevant to this example.

A Dual Process Model of Perspective Taking

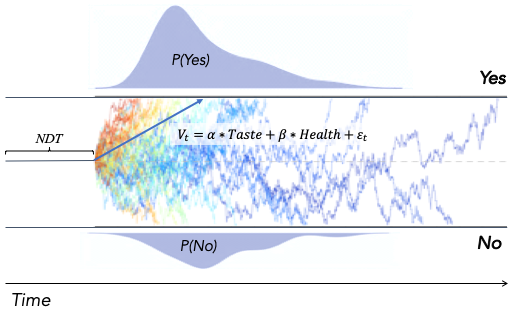

In social psychology, one of the foundational concepts underlying much theorizing is the idea that we have fast and slow systems driving our choices, and that the competition or dynamic interplay between these systems can be one reason we don't always make good choices. For example, in the domain of perspective taking, it is sometimes hypothesized that people have an "egocentric" bias. That is, they tend to rapidly and automatically assume that other people will have the same preferences that they themselves have. Of course, they can correct such biases when given sufficient reason, but the theory goes that this correction is slow and takes some effort. Thus, unless you're given plenty of time and put in the effort, you're very likely to default to using yourself as an anchor. This theory is known as the "Anchoring and Adjustment" account of perspective taking, and it makes a lot of intuitive sense

One of the primary pieces of evidence for this account comes from an analysis of response times when making choices for the self and others . In particular, researchers have observed that people often take longer to make choices for others (particularly similar others) when those choices diverge from what they themselves would have chosen compared to when those choices are the same (e.g., Tamir & Mitchell, 2013). This would seem to be evidence that making a different choice for someone else requires some extra...something, perhaps to override a naively egocentric point of view.

But there are a lot of questions one can ask about this process. For example, when does this "adjustment" mechanism activate? Does it activate more quickly for some people than others? What neural mechanisms support this adjustment mechanism? Is an adjustment mechanism even necessary to explain these patterns? Etc.

A single-process model of perspective taking

A few years ago, Alison Harris, John Clithero, and I began a project asking these kinds of questions, using the drift diffusion model to answer them. And what we found was quite suprising. Using food choices as a lens, we replicated the basic finding that people take longer when making different choices for others than they would for themselves. Yet, after doing an extensive set of modeling exercises, we found that the patterns of response time that looked so much like evidence for dual processes in perspective taking could actually be explained without assuming any kind of fast and slow systems! Moreover, neural EEG signals recorded from participants at the time of choice seemed entirely consistent with this view: value signals when deciding for others emerged at much the same time, and with a similar spatial distribution, as when deciding for the self.

What then was producing the pattern of RTs we observed? Here's the basic logic. In most studies of this sort (as in ours), researchers ask participants to make choices about a bunch of different stimuli, once for themselves, and once for another person. Then, we divide those objects based on whether the chooser made the same or different choice on trials for the self and trials for the other. For example, imagine that they said yes to a bowl of lettuce for themselves, but no to a bowl of lettuce for someone else. This trial would get put into the "Different" pile. A trial in which they said yes to Vanilla Ice Cream for both themselves and the other would get put into the "Same" pile.

So far so good. But notice that the fact that people are NOISY decision makers suggests one very simple explanation for why people might sometimes make different choices on Self and Other trials for the same food: if they aren't totally sure about the value of a food, they might sometimes say yes and sometimes say no to it, even when deciding for themselves! And guess what? These will be the trials that typically take the longest to make (because the evidence is weak)! So even if they are choosing for others in the exact same way as they would choose for themselves, we might expect some trials where their choices differed, and we'd expect this to happen more often on trials with ambiguous values and longer average RTs. And voila! You could have what looks like an anchoring-and-adjustment effect without any anchoring and adjustment - just anchoring alone would explain it.

Now, it is also the case that you could get longer RTs if there really IS some kind of anchoring-and-then-adjustment process going on. So we needed a computational model to tell us how much of the patterns we were seeing could be solely due to choice difficulty, and how much might be due to an early self-biased period of evidence accumulation followed by a later perspective-informed shift. We were encouraged strongly in doing this by some really excellent reviewers, whose critical comments pushed us to develop novel methods for analysis (so thank you, whoever you were!)

Fitting the Models

To test this, the first thing we needed to do was to develop code that could simulate the process of anchoring and adjustment (or, more generally, could simulate the process of starting out with one value for a food and then switching to another value). Here is the MATLAB function that I wrote for doing this. Note that this code takes a slightly different approach to estimating distributions of responses and RTs than what we've worked with up to this point. It uses a "transition matrix method" developed by Tavares et al. (2017) (and, independently in slightly different form, by Brunton & colleagues). This method is nice because it yields faster estimates and cleaner distributions, at the cost of slight distortions to the distribution that would have been calculated with a genuine DDM.

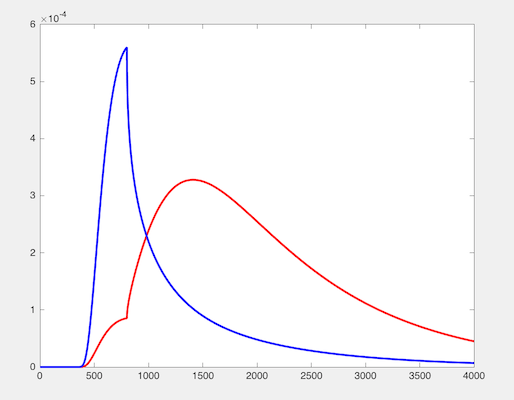

For example, here are the probability distributions for yes RTs (blue) and no RTs (red), assuming that a person starts with an initial positive evidence of +.08, and then shifts after 400ms to a negative evidence of -.04 (as might be expected if they personally like a food, but suspect another person might not).:

Note how early RTs are much more likely to be a "yes" response, while over time, this transitions into "no" responses at later RTs. These probability distributions allow us to estimate the likelihood of a given choice and RT for any combination of parameters.

To get the full likelihood of the observed data for a particular participant in a particular condition, I wrote this script. It takes as input the choices and rts to be fit, as well as a specific parameter combination, and estimates the total negative log-likelihood of the data for that parameter combination.

Finally, I wrote a script to use the DDM function and the negative log-likelihood function to perform a grid search over a large combination of possible parameter values to find the parameter combination that gets closest to maximizing the probability of the data. The script included here performs this task for an anchoring and adjustment model, which assumes that the participant starts with their own values, and then shifts at some point (possibly gradually) to a new set of values informed by their beliefs about the others' preferences.

I then compared this model to a simpler model that assumes NO shift from self to other, but instead assumes that the participant begins immediately with the values for the other person. The simpler model consists of two fewer parameters, and so receives a slightly lower "complexity" penalty using AIC or BIC scores. When we compared these values, the simpler model generally performed better for most participants.

For a full discussion of these issues, I am sharing

an appendix that we included in our response to reviewer comments, since it contains a full summary of the kinds of approaches we used to make these comparisons. You can also read the paper itself for more details, as well as some of the exciting neural results that bolstered our conclusions. I hope these materials can be useful to you as you consider using these models in your own work.

Happy modeling!

Return to main page. >>

References

Brunton, B. W., Botvinick, M. M., & Brody, C. D. (2013). Rats and humans can optimally accumulate evidence for decision-making. Science, 340(6128), 95-98.

Harris, A. et al. (2018) Accounting for Taste: A Multi-Attribute Neurocomputational Model Explains the Neural Dynamics of Choices for Self and Others. J. Neurosci. 38, 7952–7968.

Tamir, D. I., & Mitchell, J. P. (2013). Anchoring and adjustment during social inferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(1), 151.

Tavares, G., Perona, P., & Rangel, A. (2017). The attentional drift diffusion model of simple perceptual decision-making. Frontiers in neuroscience, 11, 468.