The Basic Drift Diffusion Model

Imagine I asked you whether you wanted to eat a handful of chocolate truffles.

How would you decide that the answer was yes or no? Were you able to decide immediately or did it take you a moment or two?

What about a handful of steamed brussels sprounts? Yes or no? How long did it take you to decide?

If you were like me, maybe you said yes pretty quickly to the tasty chocolate, but it took you a little bit more time to say you would eat the brussels sprouts, and you had to dredge up a reminder to yourself that they're very healthy. Or maybe for you the chocolate was a quick no and the brussels sprouts an easy yes (lucky you!).

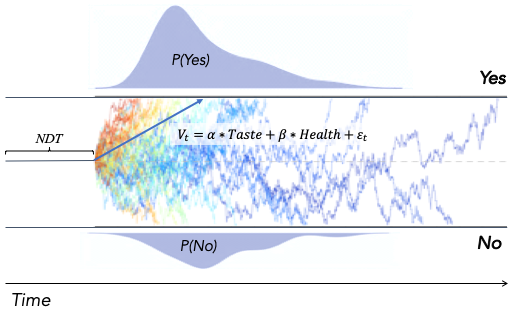

The drift diffusion model (DDM) is an algorithm designed to describe the process and dynamics by which organisms make decisions like these (and others). It has been shown to capture, with remarkable precision, both the speed and accuracy with which people make these choices (Bogacz et al., 2010; Ratcliff et al., 2016). Although the DDM was originally developed to describe decisions based on perceptual and memory processing, newer work has begun to apply these models successfully to domains that interest social psychologists, including food choice (e.g., Milosavljevic et al., 2010; Tusche & Hutcherson, 2018), altruism (Hutcherson et al., 2015; Chen & Krajbich, 2018), perspective taking (Harris, Clithero & Hutcherson, 2018), intertemporal choice (e.g., Amasino et al., 2019), and moral decision making (Baron & Gürçay, 2017).

The model at its heart is straight-forward, and consists of just a few key parameters (mathematical quantities governing the operation of the algorithm). In this tutorial, we'll cover the conceptual and theoretical underpinnings of three of these parameters (i.e., drift rate, threshold, and non-decision time), and complete some exercises designed to help you explore the influence of these parameters on the behavior of the algorithm.

The importance of noisy evidence

The fundamental idea underlying the DDM is that when your brain sees a choice option, it computes evidence about that decision and uses it to choose an action. For example, if the choice is "Color: Red or Blue?" the brain might compute something related to the strength of firing in red, green, and blue photoreceptors in the eyes. If the choice is "Chocolate: Yes or No?" the brain might compute evidence about a subjective value for the chocolate, perhaps based on firing of reward-related neurons in areas like the amygdala, ventral striatum, or medial prefrontal cortex. Let's call the overall strength of this evidence E.

Critically, the DDM assumes that this quantity E is computed at each instant in time with noise. In other words, if you continuously measured the instantaneous strength of the evidence at each time point t (let's call this quantity Et), it likely wouldn't actually be precisely E. This might be because of the intrinsic noise inherent to neural firing, dynamic and random fluctuations in attention, or even to objective fluctuations in the evidence itself (e.g., fluctuation in photons hitting the eyes, etc.). For our immediate purposes, it's less important where that noise comes from, than that it exists. In this case, we can describe the instantaneous evidence by the equation:

Et = E + σt

where σt is assumed to be random variable that is distributed normally as ~N(0,σ) (i.e., has a mean of zero and a standard deviation of σ).

What are the implications of noise for decision making? Well, I hope you've immediately grasped that it represents something of a problem for making good choices. Let's say you're trying to decide whether to eat the chocolate, and that there's a subjective "truth" about how much reward you would derive from eating it or avoiding it, which you're trying to figure out. If the brain signals this value on average as E, but does so noisily, this means you might not be able to guarantee that making your choice based on the evidence at any single moment in time would guarantee you'd make the right choice. If this concept doesn't make sense to you, or you'd like to explore its implications more using code, click here.

What is a good solution to this problem of making choices based off of noisy evidence?

Here's one possibility, which won't be where we end, but is useful as a place to start. Instead of choosing based solely on a single instantaneous Et, you could observe a whole bunch of samples of Et and average them. For example, let's say you decide to collect 100 samples of Et, which might take you, say, 100ms. You could then add them up, divide by the total, and have a good sense of their central tendency, since the average of these samples is much more likely to be close to E than any single sample. Ergo, you'd be much more likely to make the "right" choice. This idea of course is one of the fudamental principles underlying theory testing in psychology, so this concept shouldn't be super-novel to you.

Now, if all you cared about was accuracy, then this might be a great solution. Define how many samples you're going to collect (ideally a lot), and then average. But, of course, when making choices (as when conducting studies) you don't just care about accuracy. You care about how long it takes you to make a choice. Ideally, you'd want to collect just enough samples to be pretty certain you know whether E is positive or negative, and no more. This might not actually require 100 samples, especially if that evidence is pretty crystal clear relative to the noise. But it's also possible that 100 samples wouldn't be enough if the evidence is really noisy, and you certainly don't want to quit gathering evidence too soon! In other words, if you care not just about the accuracy of your choice, but also about how long you take to make it, the rate at which the evidence accumulates should matter. This quantity is known as the drift rate, and it plays an important role in determining how many samples of evidence you should collect (and therefore, how much time it will take you).

So how do you define the optimal stopping rule so that you collect only as much as evidence as you need, and no more, while still being guaranteed some acceptable level of accuracy in your choices (say, 95%)?

Here's where the second crucial parameter in the DDM comes in.

The importance of a criterion for choice

Rather than defining ahead of time a fixed number of samples of evidence you're going to collect, simply sum up the samples sequentially as you go, and after each new piece of evidence ask, "Has the sum of the samples so far achieved sufficient magnitude that I'm pretty sure whether the true value of E is positive or negative?".

For example, let's say you think the amount of variation you get from evidence sample to evidence sample tends to be between +5 and -5. So just seeing that your first sample of evidence Et=1 = +2 isn't super-informative about what you should respond. So let's take a new sample. Let's say the new sample Et=2 = +4. Again, given noise of ±5, that on its own isn't super-informative either. But together, your first two samples of evidence add up to +6. That's a bit better - it's slightly outside the range of the noise (±5). Though not by much. So let's take a third sample. +1. Again, on it's own not super-convincing. But the sum of the three values is now +7. Is that enough outside the noise to make a choice? Ultimately, we'll have to decide that for ourselves: what is the appropriate criterion or threshold to put on the accumulated evidence that we're pretty sure its value matches the sign of the true value of E, and isn't simply due to noise?

In our particular example, given that the noise is only 5, if we want to be pretty accurate, we could set the threshold for choosing much higher than that. Arbitrarily, let's say 30. It's a number that's high enough that it's unlikely that if you reach +30 or -30 in your total accumulated evidence that that's simply due to noise. Now, if you want to be really accurate, you could set that threshold even higher (say, ±60 instead of ±30). And if you cared more about arriving at any answer quickly, rather than being accurate, you could set that threshold lower (say ±10). You'd make more errors, since the ratio of the threshold to the noise is lower, but you'd be able to respond quickly. Thus, the combination of sequential accumulation of evidence plus a threshold allows you to define for yourself what kind of speed-accuracy tradeoff you want to make in your decisions.

There's also another really nice property of this stopping rule: if the evidence, or drift rate, is really strong (e.g., E=+10), it won't take very many samples to cross your threshold, and you'll be able to decide quickly. If the evidence is weak (e.g., E=+2), it'll take you longer to decide, but you'll still be more likely to achieve your desired accuracy or certainty level once you have.

And voila! A simple solution to making choices based on noisy evidence, which provides a provably optimal tradeoff between speed and accuracy under certain assumptions (see Bogacz, 2006 for more detailed discussion of this point). It defines both what choice you should make, how long it might take for you to make it, and how accurate that choice is likely to be.

To see how this algorithm is programmed, and to complete some exercises designed to test your intuitions about its implications, click here.

One more parameter: non-decision time

So far, we've talked about evidence/drift rate and threshold, but there's something else we need to consider before we can fully define both choices and observed response times in a drift diffusion model.

Let's go back to our problem of choosing whether to eat chocolate or not. Note that up to this point we've modeled the decision as starting at the moment you collect your first piece of evidence. But of course, that evidence has to come from somewhere. If it derives from, say, value-coding neurons in the brain, those neurons likely don't start firing instantly the first moment you encounter the word "chocolate." It takes a few tens of milliseconds for signals on the page to travel from your retina to your brain, another couple of tens of milliseconds for those signals to be translated into recognition and representation of the word "chocolate" and then probably a few more milliseconds for this word to trigger firing of value/evidence neurons. We can think of this sequence of events as the perceptual processing time that determines how long it takes for meaningful, decision-relevant evidence to be available to be accumulated, and it will add some time to our response, regardless of how strong the evidence is.

Similarly, from the moment the evidence crosses a threshold for choice, we still have to enact that choice by sending motor commands down through the spinal cord to the relevant bodily effectors that implement it (e.g., moving your hand to reach for the chocolate). Typically, this motor processing time is estimated to be ~80ms, and it will also add a small amount of time to the overall decision, although it shouldn't really depend on what that decision is.

When added together, these two quantities are known as the non-decision time. Usually, we aren't super-interested in the precise value of this time, but properly estimating things like the drift rate and the threshold can't be done without taking into account the non-decision time, and there are certain cases in which theory can be informed by the non-decision time, so it's useful to develop an intuition about how it shapes response times. To explore its influence click here.

You have now finished the tutorial on the basic DDM. Please return to the home page or continue to the module on the extended DDM.

References

Amasino, D. et al. (2019) Amount and time exert independent influences on intertemporal choice. Nature Hum. Behav., 3, 383-392.

Baron, J. and Gürçay, B. (2017) A meta-analysis of response-time tests of the sequential two-systems model of moral judgment. Mem. Cognit. 45, 566–575.

Bogacz, R. et al. (2006) The physics of optimal decision making: A formal analysis of models of performance in two-alternative forced-choice tasks. Psychol. Rev. 113, 700–765.

Bogacz, R. et al. (2010) The neural basis of the speed-accuracy tradeoff. Trends in Neurosci., 33, 10–16.

Chen, F., & Krajbich, I. (2018). Biased sequential sampling underlies the effects of time pressure and delay in social decision making. Nature Comm., 9, 3557.

Harris, A. et al. (2018) Accounting for Taste: A Multi-Attribute Neurocomputational Model Explains the Neural Dynamics of Choices for Self and Others. J. Neurosci. 38, 7952–7968.

Hutcherson, C.A. et al. (2015) A neurocomputational model of altruistic choice and its implications. Neuron 87, 451–462.

Milosavljevic, M. et al. (2010) The Drift Diffusion Model can account for the accuracy and reaction time of value-based choices under high and low time pressure. Judgm. Dec. Making, 5, 437-449.

Ratcliff, R. et al. (2016) Diffusion Decision Model: Current Issues and History. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 260–281.

Tusche, A. and Hutcherson, C.A. (2018) Cognitive regulation alters social and dietary choice by changing attribute representations in domain-general and domain-specific brain circuits. eLife 7, 282–35.